Download the PDF

Evidence is mounting that the US may be in a new inflationary regime, where repeated supply-side shocks - including the pandemic, war in Ukraine and higher tariffs - together with a sharp slowdown

in US immigration, are contributing to persistently above-target core US inflation.

The Federal Reserve (the Fed) now faces an increasingly delicate balancing act between its dual mandates of maximum employment and price stability. Growing concerns about the politicisation of the Fed and the integrity of other US institutions raise the risk that inflation expectations could become de-anchored over time.

Across the G10 — and Australia — there are recent signs that the post-pandemic disinflationary impulse is stalling. In this environment, bonds may no longer rally automatically at the first sign of labour market weakness. A more cautious Fed or higher inflation risk premiums on long-end bonds could challenge some of the traditional portfolio benefits of fixed income during downturns.

Despite these headwinds, we believe fixed income remains a core defensive asset. However, achieving resilience in this new environment requires investors to consider broadening their fixed income toolkit and applying more sophisticated strategies to improve defensiveness and protection. QIC’s fixed income process employs three key levers — interest rates, credit spread duration, and inflation duration — designed to provide improved diversification and defensive benefits across different market regimes.

Why inflation protection matters now

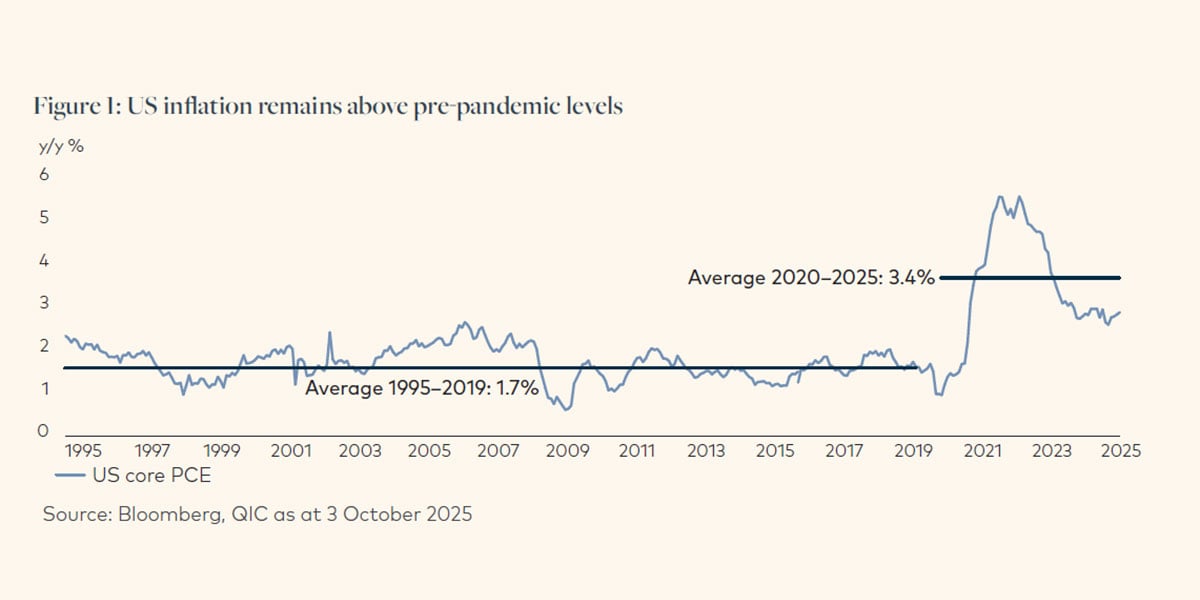

Today, US inflation remains higher than pre-pandemic levels and progress towards the Fed’s 2% core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator target has recently stalled (refer Figure 1). Tariff increases are widely expected to further add to US inflation and recent Federal Reserve business liaison suggests the pass-through from tariffs to prices is likely to be protracted.1 The sharp slowdown in US undocumented immigration since mid-2024 also adds to upside inflation risks by reducing labour supply growth.

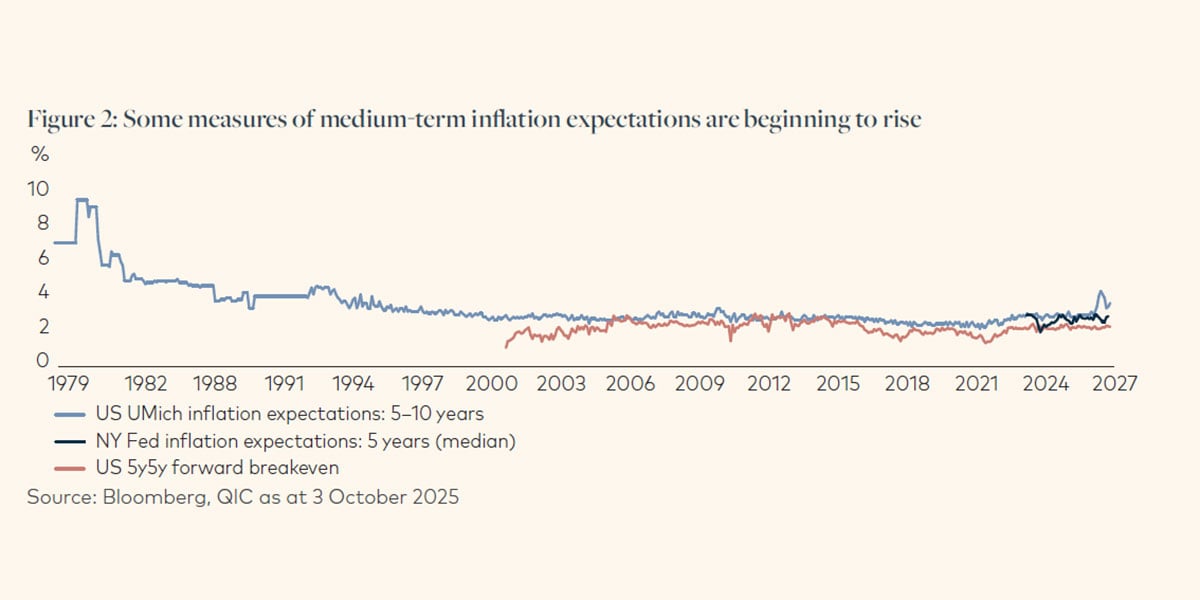

Further, since early 2025 there have been some ‘yellow flags’ that medium-term inflation expectations - after having been anchored for over three decades - are now starting to rise (refer to Figure 2).

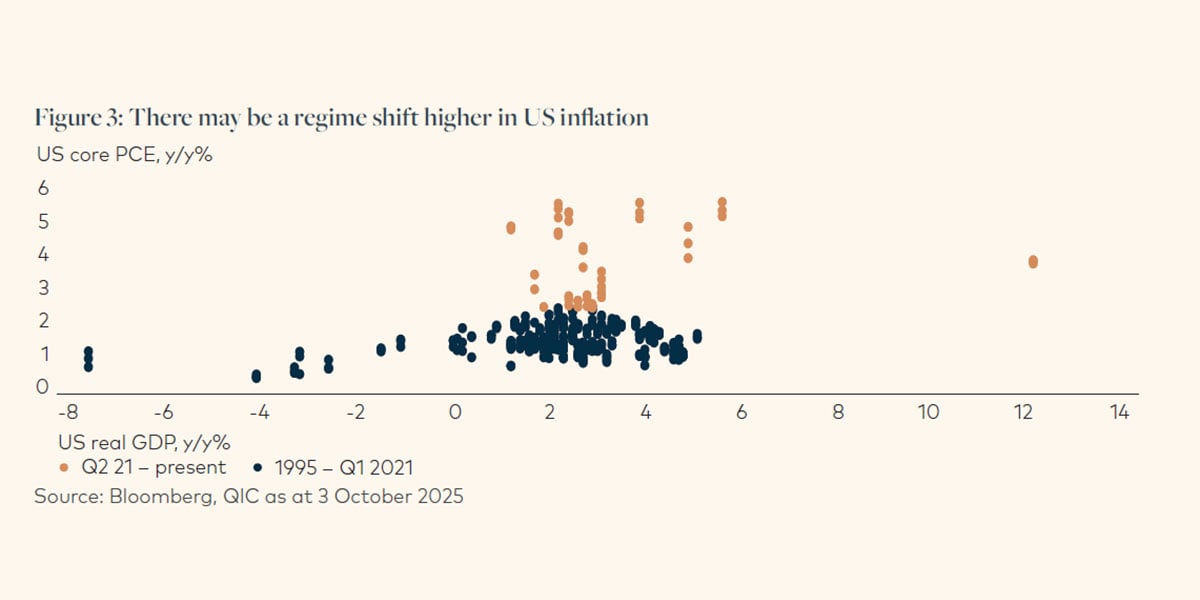

Recent, repeated supply-side shocks may have permanently reduced the economy’s productive capacity. Efforts to build more resilient - but less efficient - supply chains, alongside higher tariffs and broader deglobalisation, could mean a lasting decline in potential output. As a result, inflation may now run higher for every percentage point of GDP growth compared with pre-pandemic norms (refer to Figure 3).

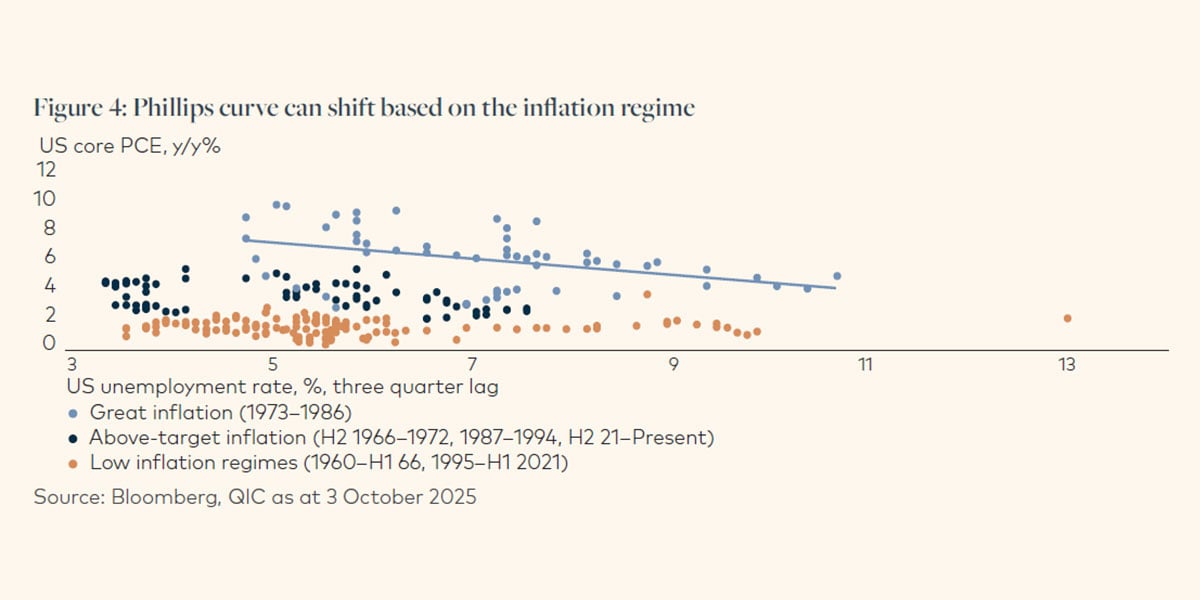

The trade-off between the Fed’s dual mandates of maximum employment and price stability could come into greater tension. In economics terms, the Phillips curve (the inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation) may have shifted higher and steeper (refer to Figure 4). With this backdrop, the Fed may no longer be able to ease monetary policy aggressively at the first sign of economic weakness if inflation remains stubbornly above its 2% target.

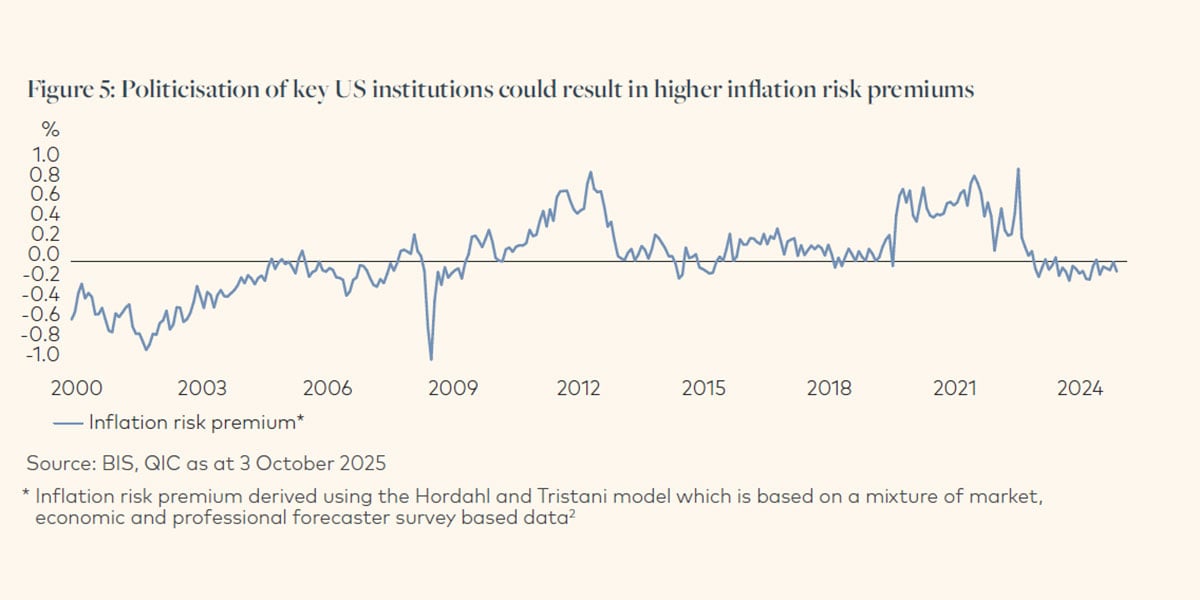

Tail risks — including greater politicisation of key US institutions or doubts about the integrity of economic data — could push inflation risk premiums higher for long-end bonds, as investors demand more compensation for the risk that inflation may exceed expectations (refer to Figure 5). There is also the risk that medium-term inflation expectations may become de-anchored if markets begin to doubt the Fed’s commitment to its inflation target.

While market focus has justifiably been concentrated on US inflation, it would be easy to miss that broader G10 and Australian core inflation has also been crawling higher this year. New Zealand and the Eurozone are the only regions where core inflation has softened since the beginning of the year.

Implications for fixed income

This combination - increasing tension between the two sides of some central banks’ dual mandates as well as greater tail risks from the politicisation of US institutions and potential for increased risk premiums - could represent a more challenging environment for fixed income investors.

Nominal bonds may not rally to the usual degree in response to economic or risk asset weakness. However, that does not mean that fixed income assets cannot provide diversification benefits to holders of risk. Rather, fixed income investors may need more sophisticated strategies to protect against upside inflation risk.

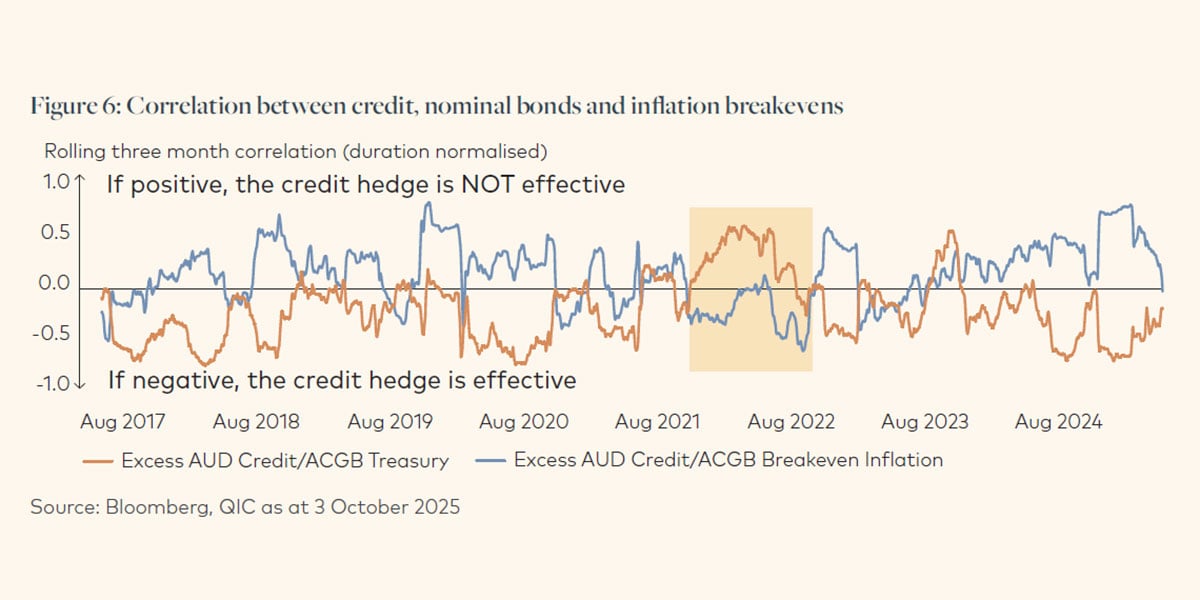

For example, in 2021–22, credit spreads widened as nominal yields rose sharply in response to aggressive interest rate hikes from central banks. In this environment, the ability to add exposure to inflation assets could have generated significant performance and importantly, provided a valuable cushion for other fixed income assets that underperformed during that period. Understanding the correlations between the three levers and being able to actively adjust portfolios is, in our view, the key to improving defensiveness of fixed income (Figure 6).

Expanding the fixed income toolkit

Dynamic fixed income strategies are needed to manage both upside inflation and downside growth risks. Inflation-indexed bonds and swaps can provide inflation protection to investors by linking interest payments (and also the principal value for bonds) to inflation. Importantly, this provides diversification in market regimes where upside inflation risks emerge.

Figure 6 illustrates the benefits to Australian fixed income investors of having both inflation and interest rate duration as a complement to credit exposure in fixed income portfolios. The chart shows the correlation between credit and nominal bonds (orange line) and inflation breakevens (blue line). Historically, investors have relied on a negative correlation between nominal bonds and credit returns but those correlations have become more unstable and less reliable in recent years. In periods when nominal bonds moved in the same direction as credit, inflation markets were often negatively correlated (shaded in yellow), providing strong portfolio diversification benefits.

Navigating inflation markets

For Australian investors, hedging inflation risks via the use of inflation-linked bonds or inflation swaps can be challenging and requires a deep understanding of liquidity, technical features (e.g., pricing methodology) and macroeconomic drivers. Inflation markets are generally less liquid than nominal markets.

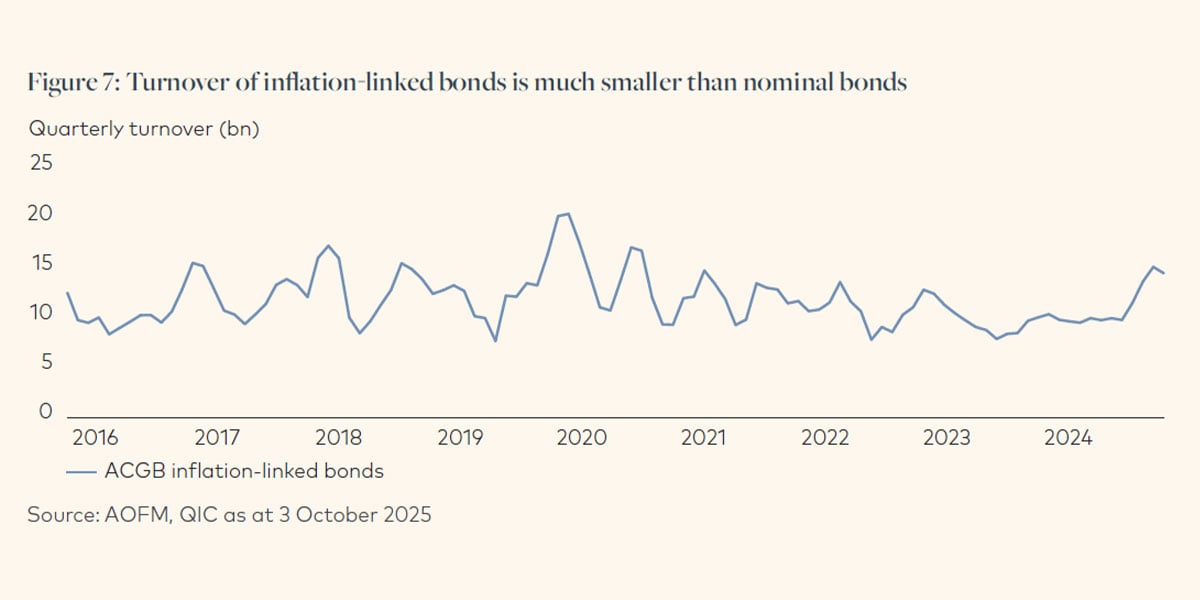

For example, secondary market monthly turnover in Australian Commonwealth Government Bonds (ACGB) inflation-linked bond markets averaged A$3.2 billion in 2024, compared to A$33 billion for ACGB nominal bonds.

Turnover in Australian inflation swaps is even lower and more sporadic (refer to figure 7). This means that a strong understanding of the flows in the market, the investor base (such as insurers and super funds), primary issuance and buyback programs as well as developing long-term relationships with active market-makers is essential.

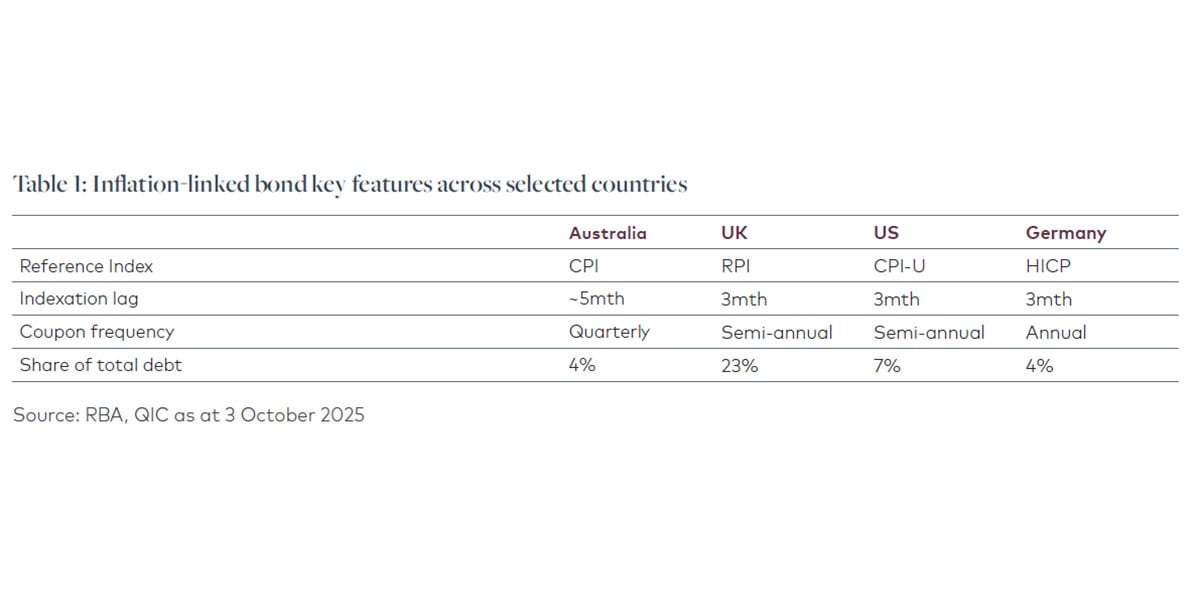

Inflation-linked bonds and swaps are also more technical in nature than nominal bonds and swaps and methodologies can differ across countries. Important inputs into inflation-linked bond pricing include the reference rate (such as the consumer price index), coupon frequency (e.g. quarterly, semi-annual or annual) and the indexation lag (e.g. 3-5 months generally). Table 1 shows how these key features vary across selected developed markets.

A deep understanding of the macroeconomic drivers of inflation markets is also required. This includes forward looking inflation expectations, inflation risk premium and the correlations to oil and risk markets.

Conclusion

There is an increasing recognition that the global economic and geopolitical order has changed post-pandemic. Investors are increasingly questioning the portfolio allocation principles that have served them well over the last 30 years.

New regimes are always defined by increased uncertainty. It is difficult to definitively say whether this new regime will result in structurally higher inflation, more volatility in inflation or no change at all. But it is our view that the distribution of risks to inflation are skewed to the upside.

Asset allocators need to consider how their fixed income assets could behave in a structurally higher inflationary regime. Our work suggests that fixed income will remain an important defensive asset, but a broader toolkit and more sophisticated strategies are required. In the future, more active and agile switching between nominal bonds and inflation hedges — as market focus switches between downside growth and upside inflation risks — may be required, making deep expertise in inflation markets an essential part of fixed income portfolio management.

Further information

QIC Limited ACN 130 539 123 (“QIC”) is a wholesale funds manager and its products and services are not directly available to, and this communication is not intended for, retail investors. For more information about QIC, our approach, clients and regulatory framework, please refer

to our website www.qic.com or contact us directly.

Do not copy, disseminate or use, except in accordance with the prior written consent of QIC.